Lynn Shoemaker’s Strike

By Rianon Prushinski

February 22nd, 1860 ushered in the Lynn Shoemakers’ Strike, also known as the New England Shoemakers’ Strike. It began with 3,000 workers walking out of shoe factories in protest, but the cause grew until 20,000 workers from over 25 towns advocated against grueling hours with little pay. The largest strike in America (up until that point) had begun.

In its early days, shoemaking was an artisan craft completed by shoemakers and their apprentices. They holed up in small buildings called ten-footers where they handmade 3-5 pairs of shoes a day, working 16 hours. Tuberculosis, often called shoemakers’ disease in those days, killed many shoemakers.

When demand for shoes began to increase, factories popped up all over Lynn to manufacture shoes globally. Shoemaking went from an artisan craft to a process of mass production. Men, women, and children worked long hours in factories with little pay. Employees worked 16 hour days, and men made about $3 a week while women only made $1 a week.

Increasing mechanized production made way for labor unrest, especially after the financial panic of 1857. Shoe factory employees lost their jobs and were out of work for some time. In the aftermath of the financial panic, they were rehired and forced to accept lesser pay. Tensions rose, and workers met at Lynn’s Lyceum Hall to discuss their grievances. Reporters noted that the meeting highlighted the workers’ passion and dedication toward the cause.

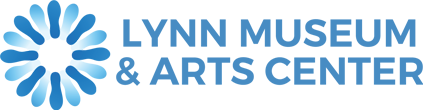

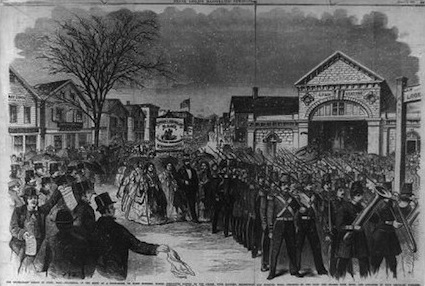

The first of Lynn’s shoe strikers walked out on February 22nd, 1860. The strikers chose George Washington’s birthday to emulate the colonies’ fight for independence from Great Britain. Workers took to the streets and sang “Yankee Doodle” as the beginning of their strike ensued. Three thousand workers marched then, but, soon, their numbers would soar.

An eye-witness to the strike, Moses Folger Rogers, expressed his disdain for the cause in a letter acquired by the Massachusetts Historical Society. Rogers hated the commotion, which had brought a few clashes with police to put the city in an “agitated & excited state.”

In addition to his fear of bloodshed, he was concerned about women’s involvement in the strike. The first strikers were men, but women joined the cause a few days later, becoming crucial to planning, execution, and morale. Rogers bemoaned that “there is a strike amongst the Ladies, who I understand propose parading the streets tomorrow to the number 2000.” The day was March 7th, and a blizzard had hit Lynn. However, women strikers refused to yield. The Great Ladies Procession marched through the streets in the snowy conditions, holding their signs high.

Unfortunately for them, strike leaders demanded wage increases for male workers only. Though the strike had dissenters, like Rogers, the community largely supported the shoemakers. The event gained national attention. Presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, gave his thoughts on the matter: “I am glad to see that a system of labor prevails in New England under which laborers can strike when they want to, where they are not obliged to labor whether you pay them or not. I like a system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere.”

Unfortunately, the New England Shoemakers’ Strike was unsuccessful. Most factory bosses refused to negotiate with the strikers over the six weeks of their protest. In the end, only 30 employers agreed to a 10% pay increase of men’s wages. However, the strike did lead to some structural changes that helped future labor efforts. These types of strikes encouraged unions, which changed labor laws for years to come. Also, voters replaced much of Lynn’s government in the next election, inputting new decision-makers in office. However, the oncoming Civil War rose over the country soon after, and the national focus shifted to wartime production.

Rianon Prushinski is a senior English major at Endicott College in Beverly, MA. She’s written collections of both fiction and nonfiction. As she concludes her career at Endicott, she’s working on her first novel (about a circus! Shhh, don’t tell…). She has grown up in Lynn all of her life, graduating from Lynn Classical High School in 2017. Her attendance at Endicott was made possible by the Learning and Leadership Program which creates collegiate opportunities for Lynn students. Currently, she is interning at Lynn Museum/LynnArts during her final semester…and she has totally gotten over that one time when she went skiing and broke her nose. Really, she has.